Hello Everyone:

It is a lovely Wednesday afternoon and time for Blogger Candidate Forum. The president's European roadshow continued today, this time it was off to Ireland and France awaits his arrival. Never one to miss an opportunity to fire off a tweet or two or three, the president demonstrated his lack history when he tweeted that the Republic of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. No. A wall separated Ireland and Northern Ireland was example of why walls work. No. The United States has the cleanest climate right now. No. In an interview with Piers Morgan, he doubled down on calling the Duchess of Sussex (and fellow L.A. woman) "nasty." No doubt the British royal family and Blogger's beloved British cousins are breathing a huge sigh of relief. D-Day ceremonies are on tap on the French coast. Let us hope all goes well. Moving on.

|

| Source: 2016 precinct from Ryne Rohla nytimes.com |

Emily Badger writes, "it's true across many industrialized democracies that rural areas lean conservative while cities tend to be more liberal, a pattern partly rooted in the history or workers' parties rooted in the history that grew up where urban factories" (nytimes.com; May 23, 2019; date accessed June 5, 2019).

The urban-rural schism is extremely acute in the United States: extremely entrenched, very hostile [link not available], and quite lopsided. How lopsided? "Urban voters, and the party that has come to represent them, now routinely lose and power [link not available] even when they win more votes" (nytimes.com: May 23, 2019). It sounds strange does it not? How does a party routinely lose votes and become the minority party in Congress even when it wins more votes?

Democrats lay blame in the Senate, Electoral College [link unavailable], and gerrymandering for their losses. Notice how they do not blame their own inability to connect with rural voters or just ignore them? However, the problem is deeper than than that, according to Jonathan Rodden, a political scientist at Stanford University: "The American form of government is uniquely structured to exacerbate the urban-rural divide--and to translate it into enduring bias against the Democratic voters, clustered at the left of the accompanying chart" (nytimes.com: May 23, 2019).

The Senate [link not available] is the problem for Democrats because it gives disproportionately more strength to rural voters. Mr. Rodden points out,

That's an obvious problem for the Democrats,... This other problem is a lot less obvious (nytimes.com: May 23, 2019).

|

| Jonathan Rodden's new book amazon.com |

In his new book, Why Cities Lose (amazon.com; date accessed June 5, 2019), Mr. Rodden describes the problem "as endemic, affecting Congress but also state legislatures; red states but blue ones, too" (nytimes.com: May 23, 2019). As the Democratic Party is caught between it the progressive and moderate wing going into the next election cycle, his analysis suggests that "if Democrats move too far to the left, geography will punish them" (Ibid). Absolutely and here is how.

In the United States, where a party's voters lives definitely matters. The reason is the majority of representatives in the House are elected from "single-member districts where the candidate with the most votes wins, as opposed to a system of proportional representation, as some democracies have" (Ibid).

The result is "Democrats have overwhelming power [link unavailable] to elect representative in a relatively small number of districts--whether for state house seats, the State Senate or Congress--while Republicans have at least enough to elect representatives in a larger number of districts" (nytimes.com: May 23, 2019). In short, Republicans are more efficiently spread out in a system that rewards this distribution.

|

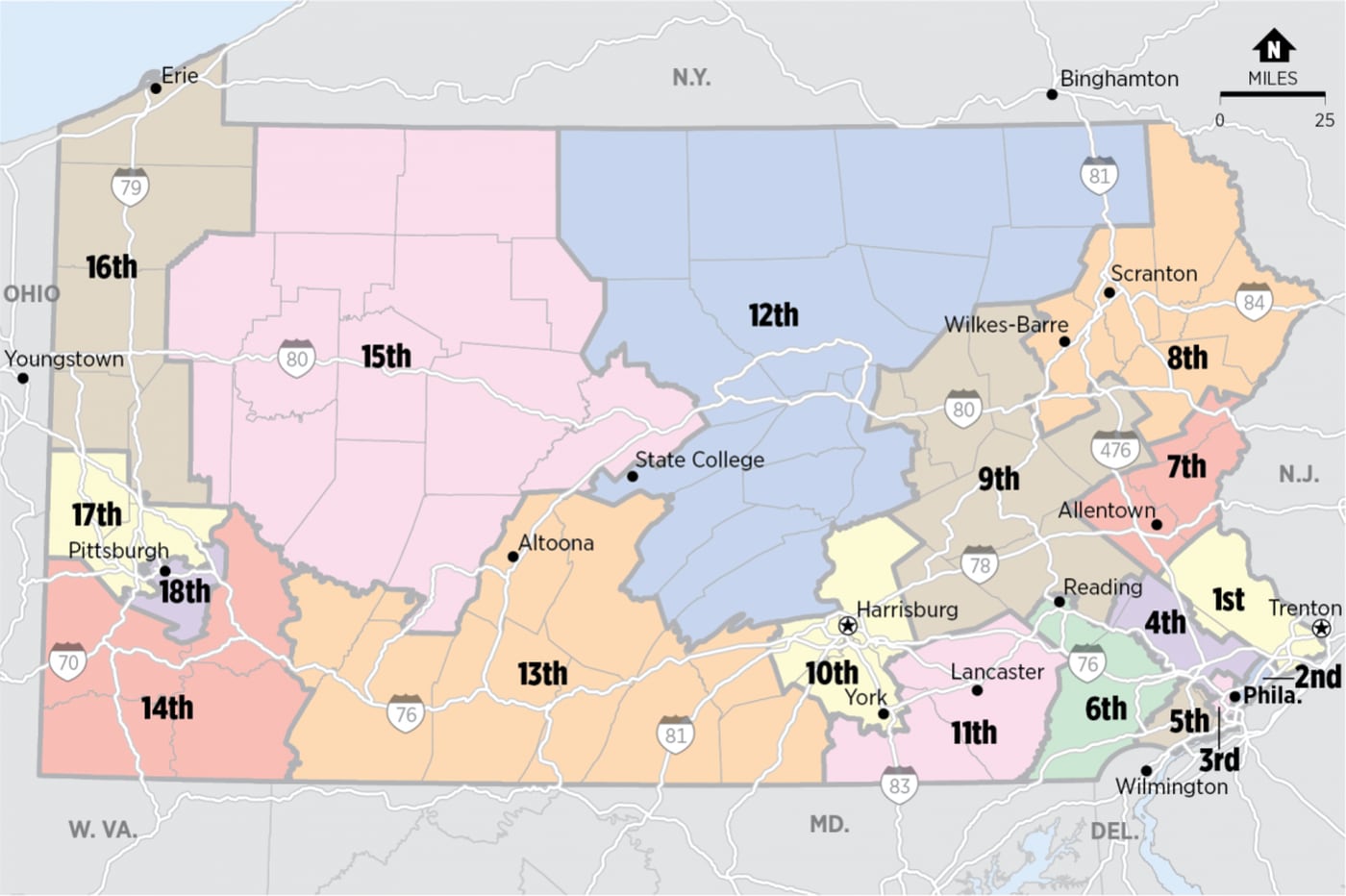

| 2018 Pennsylvania electoral map inquirer.com |

This explains why Republicans have controlled the Pennsylvania state legislature for nearly four decades, despite losing statewide elections about half that period. I also explains why Republicans are typically overrepresented in blue states like New York. It also explains why former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton only won three out of the eight Minnesota congressional districts--"districts drawn by a panel of judges" (Ibid)--even though she won the state.

For comparison sake, in the majority of European democracies, geography does not impact voting results in the same manner. Following along: lawmakers are chosen from larger districts, each with more than one representatives, giving a party proportional power. If the X Party wins at least 50 percent of the votes, how the votes are distributed is not an issue.

However, Great Britain, Australia, and Canada shares the same majoritarian system as the United States, and the urban-rural is in evidence as well. Mr. Rodden argues, "Underrepresentation of the left,..., is a feature of any democracy that draws winner-take-all districts atop a map where the left is concentrated in cities" (Ibid).

In the United States, the combination of winner-take-all districts superimposed on a map where the left in concentrated make the schism more potent. That peculiar American institution of gerrymandering allows Republicans to magnify their advantage on the political map. Democrats gerrymander as well but they do so in order to neutralize their disadvantage.

The inflexible American two-party system results in political differences that align with the urban-rural divide. Thus, the urban party is the party of gay marriage and gun control while the rural party stands for stricter immigration and abortion restrictions.

Emily Badger writes, "We keep adding more reasons to double down on geography as our central fault line, and to view our policy disagreements as conflicts between fundamentally different ways of living" (Ibid)

Recent history has clouded the consequences of all this for the Democratic Party, the majority party for most the postwar, until 1994 and the Gingrich Revolution. The Democrats were briefly able to retake the House before losing it in 2011, then regaining in the last Midterm Election by winning seats on Republican-esque territory. Jonathan Rodden correctly argue that the "Democrats need moderate 'blue dogs [link unavailable],... to overcome their geographic disadvantage" (Ibid).

"Historically, split-ticket voting has been asymmetrical" (Ibid). Many districts that swung Republican in presidential elections have voted for moderate Democrats in congressional races. The reverse is is rarely true. Republicans have seldom flipped Democratic districts. Mr. Rodden said,

They've not as a matter of survival needed to that,... Democrats need to do it even in a good year." (Ibid)

In the 2018 Midterms, Democrats squeaked out victories in those exact districts, suburbs that have a history of voting for moderate Republican candidates.

Be that as it may, split-ticket voting has become less common, as the major parties have more clearly defined their differences, and as local elections now have national implications. Both trends make it more challenging for individual Democratic candidates to divest themselves from the national party--i.e. low taxes and abortion right or Affordable Care Act and the Second Amendment. Three red-state Democratic senators, Heidi Heitkemp, Clair McCaskill, and Joe Donnelly lost their Senate seats in this kind of environment.

Mr. Rodden said,

You have this great strategy available to you as a Republican: Just talk about A.O.C. all the time,.... Talk about Nancy Pelosi. They say, 'This is what it means to have 'D' next to your name, you're signing up for that team.' That makes it so hard to be a suburban Salt Lake City, suburban Oklahoma City Democrat. (Ibid)

This strategy might work in the short term but in the long term, voters will want to know what having an 'R' next to a candidate's name means.

He found that "The median congressional district in America looks ideologically more Republican...." (Ibid). Therefore, Democrats have find a way to win in those districts, even as the progressive wing of the party is on the rise and lobbying for control of the message.

Therefore, if the Democrats hold on to the suburbs they flipped in the Midterms-a possibility as suburbia becomes more diverse and as college-educated whites gravitate towards Democrats (link unavailable)--Republicans could find themselves concentrated in rural area just as Democrats have been confined to urban areas.

If this is the case, a scenario where Republicans tightly pack their votes in rural areas and the median suburban becomes more blue, the urban party could actually benefit from geographic division. However, there is always the Senate.

For comparison sake, in the majority of European democracies, geography does not impact voting results in the same manner. Following along: lawmakers are chosen from larger districts, each with more than one representatives, giving a party proportional power. If the X Party wins at least 50 percent of the votes, how the votes are distributed is not an issue.

However, Great Britain, Australia, and Canada shares the same majoritarian system as the United States, and the urban-rural is in evidence as well. Mr. Rodden argues, "Underrepresentation of the left,..., is a feature of any democracy that draws winner-take-all districts atop a map where the left is concentrated in cities" (Ibid).

In the United States, the combination of winner-take-all districts superimposed on a map where the left in concentrated make the schism more potent. That peculiar American institution of gerrymandering allows Republicans to magnify their advantage on the political map. Democrats gerrymander as well but they do so in order to neutralize their disadvantage.

The inflexible American two-party system results in political differences that align with the urban-rural divide. Thus, the urban party is the party of gay marriage and gun control while the rural party stands for stricter immigration and abortion restrictions.

|

| Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich nationalreview.com |

Recent history has clouded the consequences of all this for the Democratic Party, the majority party for most the postwar, until 1994 and the Gingrich Revolution. The Democrats were briefly able to retake the House before losing it in 2011, then regaining in the last Midterm Election by winning seats on Republican-esque territory. Jonathan Rodden correctly argue that the "Democrats need moderate 'blue dogs [link unavailable],... to overcome their geographic disadvantage" (Ibid).

"Historically, split-ticket voting has been asymmetrical" (Ibid). Many districts that swung Republican in presidential elections have voted for moderate Democrats in congressional races. The reverse is is rarely true. Republicans have seldom flipped Democratic districts. Mr. Rodden said,

They've not as a matter of survival needed to that,... Democrats need to do it even in a good year." (Ibid)

In the 2018 Midterms, Democrats squeaked out victories in those exact districts, suburbs that have a history of voting for moderate Republican candidates.

Be that as it may, split-ticket voting has become less common, as the major parties have more clearly defined their differences, and as local elections now have national implications. Both trends make it more challenging for individual Democratic candidates to divest themselves from the national party--i.e. low taxes and abortion right or Affordable Care Act and the Second Amendment. Three red-state Democratic senators, Heidi Heitkemp, Clair McCaskill, and Joe Donnelly lost their Senate seats in this kind of environment.

Mr. Rodden said,

You have this great strategy available to you as a Republican: Just talk about A.O.C. all the time,.... Talk about Nancy Pelosi. They say, 'This is what it means to have 'D' next to your name, you're signing up for that team.' That makes it so hard to be a suburban Salt Lake City, suburban Oklahoma City Democrat. (Ibid)

This strategy might work in the short term but in the long term, voters will want to know what having an 'R' next to a candidate's name means.

He found that "The median congressional district in America looks ideologically more Republican...." (Ibid). Therefore, Democrats have find a way to win in those districts, even as the progressive wing of the party is on the rise and lobbying for control of the message.

Therefore, if the Democrats hold on to the suburbs they flipped in the Midterms-a possibility as suburbia becomes more diverse and as college-educated whites gravitate towards Democrats (link unavailable)--Republicans could find themselves concentrated in rural area just as Democrats have been confined to urban areas.

If this is the case, a scenario where Republicans tightly pack their votes in rural areas and the median suburban becomes more blue, the urban party could actually benefit from geographic division. However, there is always the Senate.

No comments:

Post a Comment