Hello Everyone:

A lovely Monday afternoon to you. Today we are going to talk about rural broadband. Before we get started, a few news items: Have you registered to vote? Yes? Good for you. No? Stop reading, go

usa.gov for voter registration information, then come back and read the post. Next, it was a bad week for former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg. First he made his debate stage debut and promptly got chewed up and spit out into a million pieces by Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA). Mayor Mike will appear on the Super Tuesday ballot

March 3, 2020. Finally today in New York City, disgraced movie producer Harvey Weinstein was convicted on two counts of sexual assault and rape. Mr. Weinstein faces trial on additional charges in Los Angeles. Onward.

Across the United States, rural communities are being excluded from contemporary society and the 21st century economy. Rural Americans want the same thing as the urban counterparts: faster, cheaper internet service that would allow them to work remotely and go online to shop, get access to the latest government information, read the latest news and current events. In 2018, the

Federal Communications Commission voted on whether mobile phone data speeds are

fast enough for online activities. The choice Americans face is: "Is

modest-speed internet appropriate for rural areas, or do r

ural Americans deserve access to far faster service options available in urban areas?" (

theconservation.com; Jan. 16, 2018; date accessed Feb. 18, 2020). It sounds like a curious question but with at least 39 percent of Americans, living in rural areas, without internet access that meets the FCC's

minimum definition of "broadband service, the question of broadband service in rural areas has taken on a sense of urgency. Shall have a look at the issue?

|

Rural broadband connection map

hcn.org |

From the beginning of the internet age, rural America has had less internet access than urban areas. Take a look at the map on the left-hand side: What you see is that as move away from urban areas, high-speed connections are less frequent and wireless phone service and signals get weaker. There are even swaths of the continental United States that have no connection whatsoever. Although internet speeds and mobile phone service has improved, one key issue remains: "Cities' services have also gotten better, so the rural communities still have comparatively worse service" (

theconservation.com; Jan. 16, 2018). National standards have not been helpful. As more of daily life takes place online, the

FCC-set minimum data-transmission speeds for broadband service has gotten faster, but not fast enough. "The current standard--

at least 25 megabits per second downloading and 3 megabits per second uploading--is deemed '

adequate' to stream video and participate in other

high-traffic online activities" (

theconservation.com; Jan. 16, 2018). However, not even these FCC-set minimums are available in rural areas. What is needed is a comprehensive national broadband plan.

Since the thirties, lawmakers have know that rural communications is a

market failure (

nytimes.com; Feb. 6, 2019; date accessed Feb. 18, 2020), something that results when "private companies cannot or will not provide a socially desirable good because of a lack or return on investment (Ibid). During the thirties utility companies--telephone and electric companies--hesitated to provide service to rural America, citing sparseness of population and vast geography. As a result, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law the

Rural Electrification Act of 1936 to provide loans and grants to rural utility companies. The Rural Electrification Act was a major success: "Within 20 years,

65 percent of farmers had a telephone and 96 percent of them had electricity" (Ibid). In the 21st century, we have a new problem in rural communications, this time it is broadband internet.

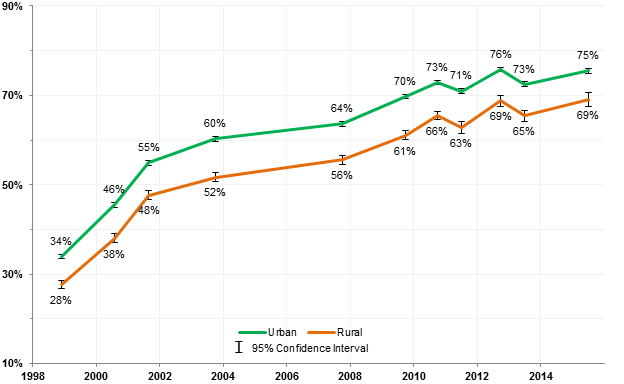

The Center for Rural Affairs reports,

The Pew Research Center finds that only 63 percent of rural Americans have a broadband internet connection at home, and 24 percent of rural adults consider access to high speed a major problem in their local community... (

cfra.org; Jan. 2, 2020; date accessed Feb. 18, 2020)

University of Virginia professor Christopher Ali wrote in 2019,

...In 2017, a full 30 percent of rural Americans (or 19 million people) and 21 percent of farms lacked broadband access.... We need a national rural broadband policy, demonstrating that the United States is serious about becoming a fully connected nation (

nytimes.com; Feb. 6, 2019)

The Clinton administration replaced the Rural Electrification Administration with the Rural Utilities Service, which has subsidized internet connectivity since 1995 (Ibid). The Federal Communications Commissions provides an annual

$8.8 billion for broadband service to rural, tribal, and low income communities, with at least

$4.6 billion designated for rural. The Rural Utilities Service (an agency of the Department of Agriculture) annually awards

$800 million per year in rural broadband loans and grants. In the summer of 2018, Congress allocated an additional

$600 million to subsidize broadband expansions to the most underserved communities. This was an addition to the

$7.5 billion rural broadband loans and grants allocated by the 2009 Recovery Act.

Thus, the lack of broadband service in rural communities is not a matter of money, that is obvious from the billions of dollars annually awarded in grants and loans from the F.C.C. and the R.U.S. The real issue is "rural America has not seen broadband deployed and adopted at the same speed and effectiveness that it had with electricity and telephone service almost a century ago" (

nytimes.com; Feb. 6, 2019). The problem is the lack of coordination in federal policies, which has allowed the telecommunications companies to receive a large chunk of the fund with little in the way regulatory accountability. The vague set of loan and grant guidelines make it difficult for communities and, shockingly some states have laws actively prohibit or throw up obstacles to prevent towns and cooperatives from wiring their communities. (Ibid).

Rural Minnesota is good place to see where and how federal broadband policies have succeeded. Minnesota is a national leader in broadband deployment plans. It allows business professionals to reduce the cost overhead that comes with having to maintain a separate office just to digitally file paperwork and with a dedicated WiFi service. It helps keep rural Minnesota student on top of their school work because about

70 percent of teachers assign homework that requires an internet connection.

Nearly every state has some sort of broadband deployment plan. However with so many plans come infinite definitions of what broadband is, target speeds, eligibility requirements for, and a myriad of unique priorities. Thus what is needed is a comprehensive national rural broadband plan. Prof. Christopher Ali writes,

Standardizing state rural broadband policies isn't enough: We need a plan to identify and galvanize stakeholders--not just the major telecommunications companies--to inspire change in our current policy approach and democratize the funding process, and to champion the cause of rural broadband across the country.... (

nytimes.com; Feb. 6, 2019)

A national comprehensive rural broadband plan would designate a single agency--ideally the Rural Utilities Service with offices in every state--as main coordinator for broadband. Right now, rural broadband service is handled by the F.C.C. and the Rural Utilities Service, who are two different agencies with conflicting agendas in charge of allocating a lot of money. Goes without saying, a one agency would definitely reduce federal expenditures, coordinate and encourage more data sharing, collaboration and coordination between the agencies.

This plan would require creating a new national broadband map, using minute data rather than broadband providers' reports of advertised speeds instead of actual speeds to the F.C.C., and where broadband use is determined by census tracts rather than individual households. Prof. Ali observes,

The F.C.C., which manages the current national broadband map, has grossly overestimated broadband deployment throughout the country because when a single building in a census block is reported to have broadband, the entire block is considered "served" (Ibid)

Designating a single agency would streamline the application process from the F.C.C. and subsidies from the Rural Utilities Services, making it easier for smaller companies to file.

Prof. Ali's suggestion for a national broadband plan also requires a change in the relationship between the telecom companies and federal subsidies. He writes,

...A national rural broadband plan would democratize the rural broadband subsidy system, abandoning the legacy rules that force the Rural Utilities Service and the F.C.C. to give the bulk of subsidies to the major telecommunications companies, which deliver only the bare minimum speeds to comply with the law. This money should be provided on a competitive basis without reserving the bulk for major companies and leaving smaller ones, like local independent providers, cooperatives and municipalities to fight for the scraps (Ibid).

One example is CenturyLink which receives over

$505 million a year from the F.C.C. but it is only legally required to provide the turtle-slow download speed of 10 megabits per second and upload speeds of one megabit (

nytimes.com; Feb. 6, 2019). There are cooperatives that mount heroic efforts to wire their communities. Alliance Communications in Rock County, Minnesota manages the fiber optic network and The People's Rural Telephone brought fiber-optic broadband to McKee, Kentucky, one of the poorest communities in the state. What both these companies, and ones like them, have in common is a genuine desire to serve their members with a public serve rather than a quick return on their investment. All too often, there are too many people who are left out of the discussion on who benefits and how from broadband connection in the digital age of American agriculture.

A national comprehensive rural broadband plan would allow the United States to show the global marketplace that it serious about being competitive in the global marketplace. The current lack of universal broadband means that the U.S. remains behind the competition in community connectivity, agriculture, data procession, telemedicine, education, and a variety of other industries. The lack of connectivity means the U.S. has no stake in global competition and we are continuing to lose ground because the major telecommunications companies receive the lion's share of funding and fail to deliver. The United States loses because the agencies in charge of rural broadband do not have an accurate census of who has and does not have broadband.

Federal policies must change so that they support cooperatives like Alliance Communications and The People's Rural Telephone, who are wiring their communities despite the lack of a coordinated federal effort.