Hello Everyone:

It is a very lovely Monday afternoon and a fresh week on the blog. A big congratulations to Team USA as they continue to roll through the 2019 FIFA Women's World Cup Tournament with a win over Team Spain. Next up is the host country Team France on Friday. Should be a great game. Until then, let us talk about why workers without university degrees are leaving the big cities.

Big cities offer myriads of exciting opportunities, especially for workers with university educations. Cities, like Seattle, Washington, are centers for cutting edge technology and progress. You would think that there is something for everyone but the big cities are losing people to other parts of the United States because there just is not something for everyone.

In April, the Census Bureau confirmed this dynamic. Eduardo Porter and Guilbert Gates write, "For the first time in at least a decade, 4,868 more people left King County, Wash--Amazon's home--than arrived from elsewhere in the country" (

nytimes.com; May 21, 2019; date accessed June 18, 2019). The numbers tell the tale.

Amazon's hometown was not the only place that lost people to domestic migration. Santa Clara County, the epicenter of Silicon Valley lost 24,645 to domestic migration for ninth year in the wall. This trend is not confined to technology hubs.

In 2018, eight out of the ten largest metropolitan areas, including those near New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Miami saw people move to other places. This is an increase from seven in 2016, five in 2013 and four in 2010 (Ibid). To give you some sense of how serious the situation is, "Migration out of the New York area has gotten so intense that its total population shrank in 2018 for the second year in a row" (Ibid).

The chart on the left (viewed more fully at

nytimes.com; May 21, 2019) show that in 2017, more people left 30 out of the 44 largest counties (measured in millions) and moving to smaller counties (also measured in million). For example, in 2017, Los Angeles County saw its population drop by over a million people while Clark County, Nevada experienced a population increase of nearly 2 million people (Ibid). The increasing flow of people out of the largest counties highlights just how uneven the distribution of opportunities have become,

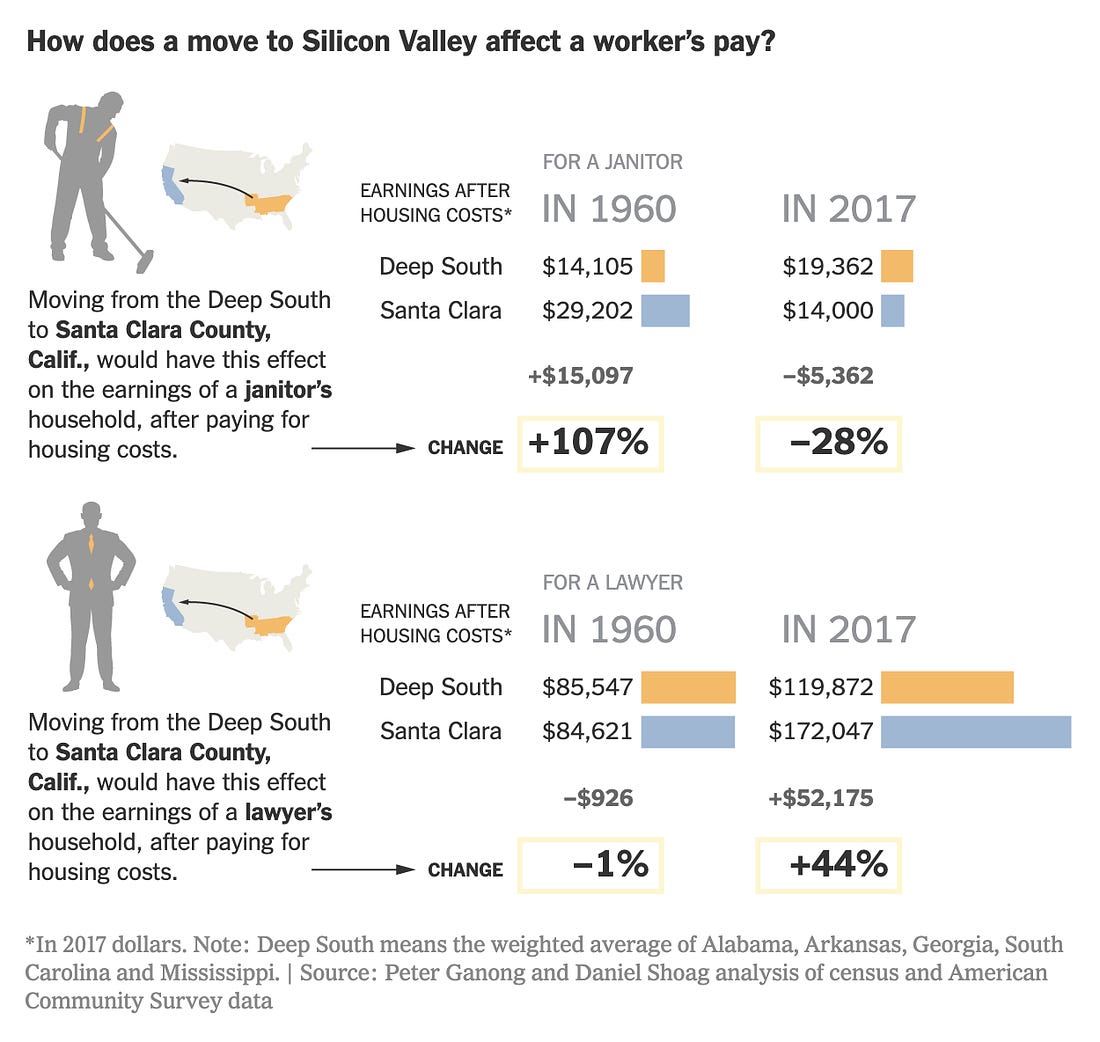

Silicon Valley cities--i.e. Mountain View, San Jose, and Palo Alto to give a few examples--may offer great opportunities for people with professional degrees looking for work in the tech companies. The reporters write, "The median family in that county [Santa Clara, California] makes $122, 700 a year, In King County it us $105, 512, way above the national median of $76,000" (Ibid). That is fantastic if you are an engineer or programmer but what if you are a janitor? Or, for that matter, anyone without a university degree? Let us consider the janitor for a moment.

In the sixties, a janitor from the Deep South--i.e. Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, South Carolina, and Mississippi-- could double his income, after housing costs, even after accounting for housing costs. However, over the last fifty years, our hypothetical janitor's earnings has grown more slowly in Santa Clara and King County (south of Santa Clara) than in the Deep South. This fact disrupts the prosperity distribution around the United States. Let us compare the affect on the janitor's pay to the affect on a lawyer's pay.

Eduardo Porter and Guilbert Gates write, "Today it makes a lot of sense for a lawyer to move to Silicon Valley from the South. The additional pay will more than compensate for the higher cost of housing" (Ibid). However, if a janitor moves, say from Mississippi to Palo Alto, could expect to see a household, after housing costs, drop by more than half (Ibid).

The disparity of economic opportunity for workers on either side of the university spectrum is not a new trend. However, it is only now being understood in terms of how it has reconfigured the reasons for internal migration: Moving for a better work opportunity is not what it used to be.

Forty or fifty years ago, a high school diploma could mean a good job in the city than in a small town. Not only did workers at the bottom of the wage scale--i.e. janitors or cashiers at convenience stores--make more money but were able to take advantage of office jobs that required little or no formal university education and paid middle class wages.

Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui recently observed their article, "What if Cities Are No Longer the Land of Opportunity for Low-Skilled Workers?" (Ibid; Jan. 11, 2019), cited the work of M.I.T. economist David Autor (Ibid), the big cities are no longer a magnet for workers without a four-year degree. They will earn no more in New York or the Bay Area than they would in small town Deep South.

The clerical jobs that once attracted high school educated workers are mostly gone, replaced by computer software or outsourced. Additionally, the wage bump that janitors and cashiers experienced in the big cities have by-and-large disappeared. Further, those who had middle-income jobs have experienced a decrease in wages and are competing for jobs at the bottom of the wage scale.

The reporters write, "And even as big-city wages flatlined for workers without requisite college degree, big-city housing prices soared ahead" (Ibid; May 21, 2019)

|

Housing Price Index 1975=100

Source: Federal Housing Finance Authority

nytimes.com |

Peter Ganong of the University of Chicago and Daniel Shoag of Harvard authored the paper,

Why Has Regional Income Convergence in the U.S. Declined (

scholar.harvard.edu; Jan. 2015; date accessed June 24, 2019), in which they suggest "that housing costs are a principal driver of the change in migration decisions: As the highly educated have flocked to superstar cities, they have pushed housing cities, they have pushed prices way beyond the reach of people earning less" (

nytimes.com; May 21, 2019; date accessed June 24, 2019).

Increasing rents impacts everybody but housing costs sucks a greater share of the income of the poor. Returning to our example of the janitor and lawyer for a moment, "In 1960, housing absorbed 17 percent of a janitor's household earnings in King County, compare with 9 percent of a lawyer's, according for Mr. Ganong. By 2017, lawyers' households had to pay almost 15 percent of their incomes. Janitors' households had to pay 38 percent" (Ibid).

Migration to rich and poor places

In 1940, university educated and less-educated workers migrated from low-income areas to more affluent one, where wages were higher. By 2016, domestic migration sharply declined. However, while the university educated were still more likely to move to more affluent areas, the less-educated stopping moving to those areas because of the lack of opportunities.

The reporters surmise, "Given the changing geography of economic, the new pattern of migration starts making sense" (Ibid).

During the mid-20th century, affluent urban clusters were magnets for people across the educational spectrum. Moving to the big city for a good job was considered a sound decision for someone with some high school education as well as a university graduate.

Over time, that attraction ebbed even for highly educated workers. Changes in the methodology used by the Census Bureau to record domestic migration--"in 1940 it asked people where they were five years ago; in 2016 it asked where they were the year before"(Ibid)--reduced the reported rates of migration. Yet, migration for work has decreased significantly over the last few decades. Eduardo Porter and Guilbert Gates writes, "In 2016, more people with bachelor's degree or more left the nation's richest metropolitan areas than arrived seeking opportunities there" (Ibid). The reason was "the rent's too damn high" for them as well. Increasing housing costs was also a deterrent. For workers without a university or college education this was particularly true. Cities like New York or Los Angeles were no simply no longer a viable option.

There is no one solution to make cities magnets of opportunity for the working class. The jobs that offered a chance at upward mobility for individuals without a university degree no longer exist and will not return. Hope exists in policy changes. The reporters write, "Relaxing zoning regulations to make it easier to build could slow rising rents ensuring that the housing supply keeps up with demand" (Ibid). Even that prospect looks bleak.

The recently shelved SB 50 in California would have forced cities to permit denser housing units closer to public and eliminated density limits in affluent neighborhoods closer to job centers and good schools. The bill was opposed by local governments and homeowners who opposed higher density living requirement--as well as rising property values.

Eduardo Porter and Guilbert Gates predict that eventually the premium placed single-family homes will diminish in the United States' marquee cities but until then, it might be better for workers with a university degree to look elsewhere.